6 months ago by @sihilel.h

Building Real-Time Multiplayer Games with AWS CDK

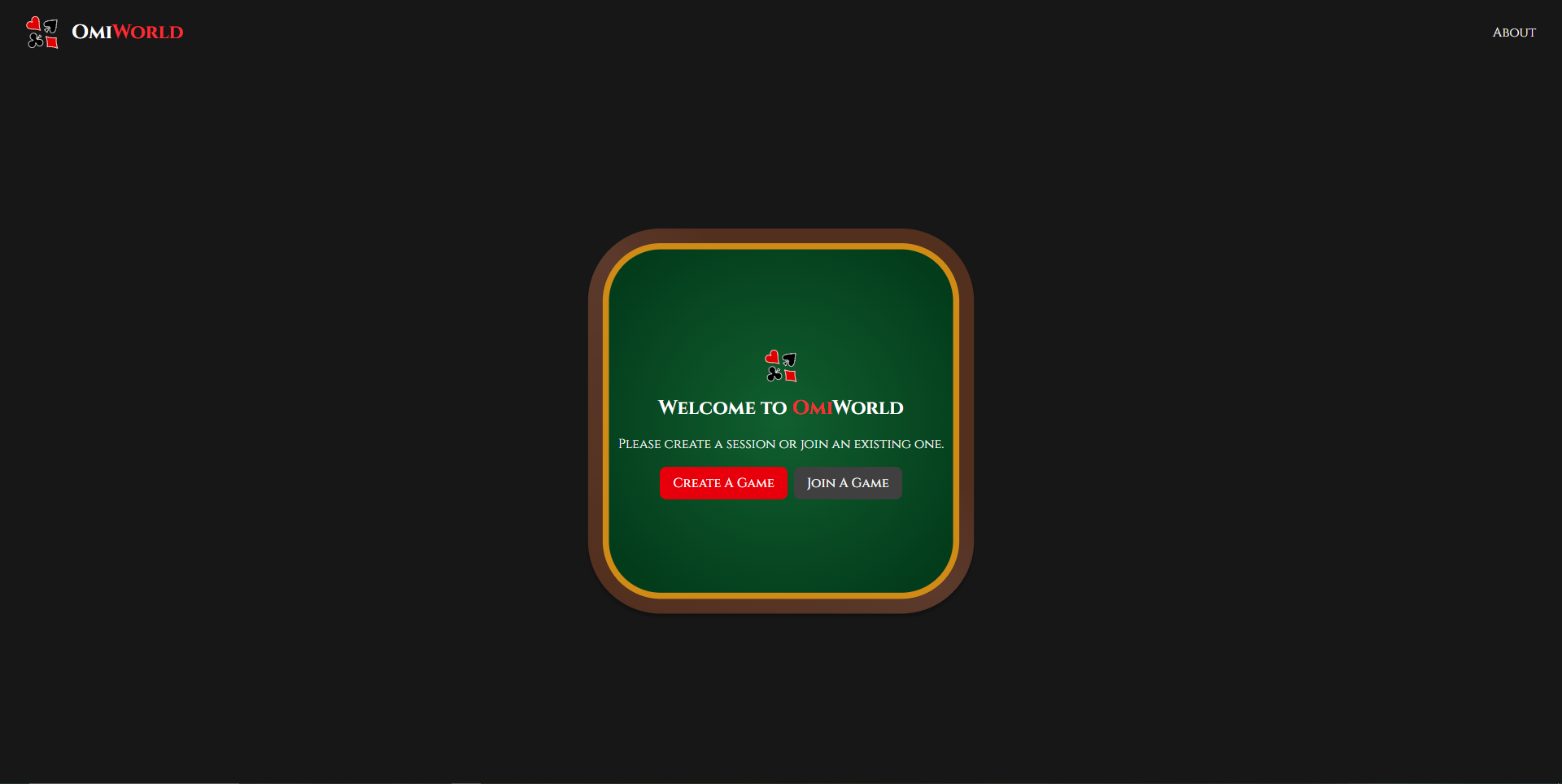

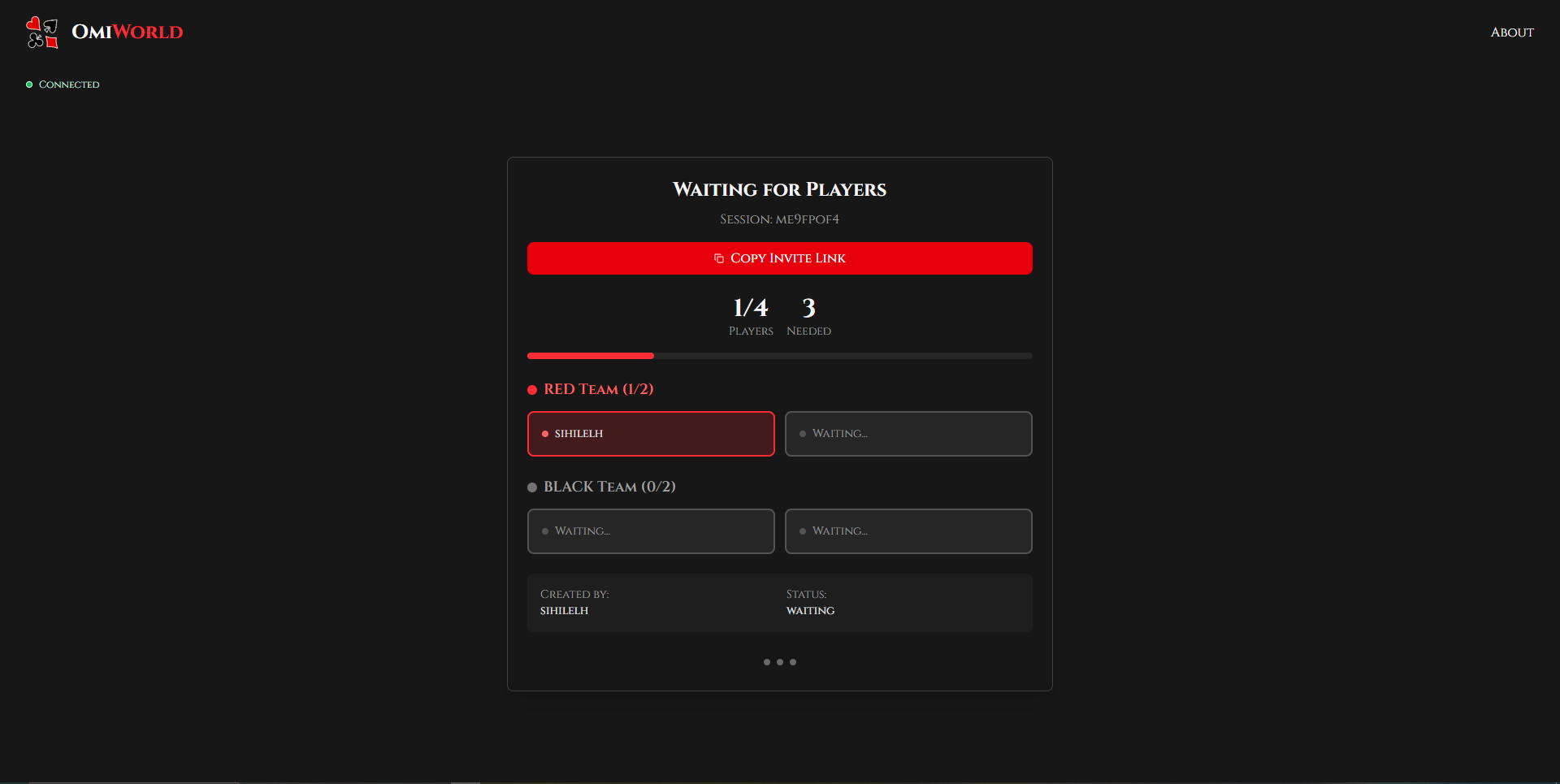

A practical deep-dive into AWS CDK, WebSocket synchronization, and serverless architecture through building OmiWorld—a multiplayer card game. Includes code examples, architectural decisions, seed-based shuffling implementation, and lessons learned from deployment to production.

Building OmiWorld: Real-Time Multiplayer with AWS CDK

I built a multiplayer version of Omi, a Sri Lankan card game I first played at my grandmother's funeral. The goal was simple: learn AWS CDK by building something that actually required multiple services working together in real-time.

Play it here: play-omi-world.web.app

The Problem with the AWS Console

My senior engineer sent me a repository during my internship—Lambda functions, DynamoDB tables, API Gateway endpoints, all interconnected. I'd used AWS before, but always through the console: click through nested menus, configure settings across different pages, copy ARNs into text files, paste them somewhere else, pray you didn't miss a permission or security group.

The repository he sent had dozens of resources. Looking at the AWS dashboard, I couldn't visualize how they connected. Which Lambda triggered which? What permissions did each role have? How would I recreate this in another AWS account?

"How do we manage all of this?" I asked.

"CDK," he said. "We code our infrastructure."

That answer didn't click until I saw the codebase. TypeScript files defining entire AWS architectures—Lambda functions, DynamoDB tables, API endpoints—all version-controlled, all deployable with a single command. No manual clicking. No ARN hunting. No "which security group did I attach to this?"

I needed a project to understand this properly. Not a tutorial, but something complex enough to require multiple AWS services working together. Something real-time. Something multiplayer.

I thought of Omi.

What Is Omi?

Omi is a 4-player card game common in Sri Lanka, particularly at funerals. I first played it at my grandmother's funeral, where family and friends gathered to stay together through the night. The game isn't about winning—it's about presence, about staying awake together, about having something to do with your hands while you process grief.

Four players, partners sitting across from each other, trying to win tricks with the right cards at the right time. The rules are simple enough to learn by playing, complex enough that strategy matters. I knew these rules by heart, which meant I could focus entirely on the technical challenge: converting a traditional card game into networked, real-time code.

Why CDK Changed Everything

Here's what that means in practice. Creating a Lambda connected to API Gateway through the console:

- Navigate to Lambda, create function, configure runtime and permissions

- Navigate to API Gateway, create API, create resource and method

- Configure Lambda integration

- Set up CORS manually

- Deploy to stage

- Copy invoke URL and manually update your frontend config

- Repeat for every endpoint

- Document all this somewhere so you remember what you did

With CDK:

const sessionLambda = new lambda.Function(this, 'SessionHandler', {

runtime: lambda.Runtime.NODEJS_18_X,

handler: 'session.handler',

code: lambda.Code.fromAsset('lambda'),

environment: { TABLE_NAME: table.tableName }

});

const api = new apigateway.RestApi(this, 'OmiApi');

const sessions = api.root.addResource('sessions');

sessions.addMethod('POST', new apigateway.LambdaIntegration(sessionLambda));

The relationships are explicit in code. The Lambda knows about the table because we passed table.tableName. The API knows about the Lambda because we created the integration right there. Change the table name? The environment variable updates automatically. Deploy to a new AWS account? Everything recreates itself identically. Want to add another endpoint? Add three more lines.

This is the revelation: infrastructure isn't something you configure through a dashboard—it's a system you design, and CDK lets you express that design the same way you write application code.

The Architecture

Zustand + Firebase] -->|REST API| B[API Gateway] A <-->|WebSocket| B B --> C[Lambda Functions] C --> D[DynamoDB] E[Cognito Auth] --> A

Zustand + Firebase] -->|REST API| B[API Gateway] A <-->|WebSocket| B B --> C[Lambda Functions] C --> D[DynamoDB] E[Cognito Auth] --> A

DynamoDB stores game sessions and player states in a single table. Lambda functions handle game logic—creating sessions, joining games, playing cards, validating moves according to Omi rules. REST API endpoints for HTTP requests like fetching game state. WebSocket connections for real-time updates when players make moves. Cognito handles authentication. React with Zustand manages the frontend state, hosted on Firebase.

The WebSocket piece was crucial. When a player puts down a card, every other player needs to see it immediately. REST APIs with polling feel laggy and waste resources. WebSockets maintain persistent connections, allowing the server to push updates the instant they happen.

Setting up WebSocket API Gateway through CDK was surprisingly straightforward:

const webSocketApi = new apigatewayv2.WebSocketApi(this, 'OmiWebSocket', {

connectRouteOptions: { integration: new WebSocketLambdaIntegration('ConnectIntegration', connectLambda) },

disconnectRouteOptions: { integration: new WebSocketLambdaIntegration('DisconnectIntegration', disconnectLambda) },

defaultRouteOptions: { integration: new WebSocketLambdaIntegration('DefaultIntegration', messageLambda) }

});

Three Lambda functions: one for handling new connections, one for disconnections, one for processing messages. The API Gateway routes WebSocket events to the right Lambda, and those Lambdas can broadcast updates to all connected clients.

Game State: Server as Source of Truth

Zustand manages state perfectly on the frontend—lightweight, intuitive, instant updates for UI animations and interactions. But it lives entirely in memory. Refresh the page and it's gone.

In a multiplayer game, this creates a critical problem. The game continues on the server while your client has amnesia. You'd have no idea what cards have been played, whose turn it is, or what the current score is.

My first instinct was localStorage. Store the game state locally, reload it on refresh. But localStorage has a fatal flaw: it captures state at the moment you save it. If another player makes a move while you're refreshing, your localStorage contains outdated information. You'd reload with the wrong game state, make decisions based on stale data, and the entire system would drift into inconsistency.

The solution: treat DynamoDB as the single source of truth. On page load, the frontend makes a REST API call to fetch the current game state:

// Lambda handler

export const handler = async (event) => {

const sessionId = event.pathParameters.sessionId;

const session = await dynamoDB.get({

TableName: 'OmiSessions',

Key: { sessionId }

}).promise();

return {

statusCode: 200,

body: JSON.stringify(session.Item)

};

};

The frontend hydrates Zustand with this authoritative data. Now it doesn't matter what happened while you were gone—you're always resyncing with reality. Local state provides instant UI feedback (card animations, turn indicators), while the server state ensures nobody's client drifts too far from the truth.

This pattern—local state for reactivity, server state for authority—became fundamental to the entire application.

Technical Side Quest: Seed-Based Shuffling

I made an interesting detour with card shuffling. The straightforward approach: shuffle the deck server-side, store the resulting card distribution in DynamoDB. Simple, works fine.

Instead, I implemented seed-based deterministic shuffling. The server generates a random seed and stores only that integer. The actual shuffle happens deterministically from the seed:

function shuffleDeck(seed: number): Card[] {

const rng = seedRandom(seed);

const deck = createDeck();

for (let i = deck.length - 1; i > 0; i--) {

const j = Math.floor(rng() * (i + 1));

[deck[i], deck[j]] = [deck[j], deck[i]];

}

return deck;

}

The same seed always produces the same shuffle. This was inspired by Minecraft's world generation—same seed, same world, every time.

Was this overkill for a card game? Absolutely. But it was a perfect excuse to understand how deterministic randomness works and why games use seeds for reproducibility. Instead of storing 52 card positions per game in DynamoDB, I store a single integer. The practical benefit is minimal, but the learning was valuable: understanding how to use pseudorandom number generators with seeds, how to ensure the same algorithm runs on both client and server if needed, and how to design for potential future features like game replays or bot training.

Sometimes the best learning happens in these technical side quests—problems you create for yourself to explore a concept, even when a simpler solution would suffice.

WebSockets in Action

Getting WebSockets working felt significant. I opened four browser windows, logged in as four different test users, and started a game. Player 1 plays a card. In the Lambda function:

const connections = await getActiveConnections(sessionId);

await Promise.all(connections.map(conn =>

apiGateway.postToConnection({

ConnectionId: conn.connectionId,

Data: JSON.stringify({

type: 'CARD_PLAYED',

card: playedCard,

player: playerId,

currentTrick: updatedTrick

})

}).promise()

));

The card appeared instantly in all three other browser windows. No delay, no polling, no manual refresh. Just immediate synchronization across all connected clients. That moment—watching the same event propagate across four windows simultaneously—validated the entire architecture.

WebSockets do come with their own challenges. Connections can drop. Users lose internet. Browsers go to sleep. The reconnection logic is still incomplete—right now, if your WebSocket disconnects mid-game, you need to refresh to rejoin and fetch the latest state. It's functional but not elegant.

What CDK Actually Gave Me

Before this project, AWS felt like an overwhelming constellation of services, each with its own console, its own configuration maze. CDK reframed it entirely. Infrastructure isn't something you fight with through a GUI—it's a system you design and express in code.

The benefits compound quickly:

- Version control: Your entire infrastructure is in Git. You can see what changed, when, and why.

- Code review: Infrastructure changes go through the same PR process as application code.

- Reproducibility: Deploy the exact same stack to dev, staging, and production with different configuration values.

- Discoverability: Need to know which Lambda has access to which DynamoDB table? Just search the codebase.

- Types: TypeScript catches configuration errors before deployment, not after.

The gap between "I need to learn AWS" and "I understand how these services connect" is smaller than it seems. The services are well-documented. The patterns—Lambda + API Gateway, DynamoDB single-table design, WebSocket broadcast logic—are established. What made the difference was building something real that required these services to work together toward a concrete goal.

The Result

OmiWorld isn't perfect. The UI could be smoother. The mobile experience needs work. The reconnection logic needs improvement. But it's real and deployed. You can visit play-omi-world.web.app, create an account, start a session, invite three friends, and play Omi from anywhere in the world. The entire infrastructure—every Lambda, every API endpoint, every DynamoDB table—exists as TypeScript code in a GitHub repository, deployable to any AWS account with cdk deploy.

That's what this project taught me: complex systems become manageable when you break them into well-defined pieces and express those pieces clearly. CDK gave me the tools to do that. Building something real gave me the context to understand why it matters.

Source code: github.com/sihilelh/omi-world

Fork it. Deploy it. Build your own multiplayer game. The hardest part is deciding to start.

Here Are Some Screenshots