3 months ago by @sihilel.h

Bringing Orchestrator to the Web with Rust and WebAssembly

Learn how I converted a Rust audio synthesizer to WebAssembly for the web. Covers wasm-pack integration, monorepo architecture, piano roll UI, and browser memory management with real performance considerations.

Building the Orchestrator CLI tool taught me how digital audio synthesis works at the byte level. The project solidified my understanding of Rust and gave me practical experience implementing complex audio pipelines. After completing it, I wanted to explore WebAssembly's promise of near-native performance in the browser. The goal was to bring the same audio synthesis capabilities to a web interface where anyone could experiment without installing anything.

WebAssembly is a low-level binary instruction format that serves as a portable compilation target for programming languages. In practice, this means compiling Rust code into a format that runs in web browsers at speeds approaching native applications. The theoretical promise was compelling, but I needed to prove it worked for real-time audio synthesis.

Why Retrofitting the Existing Codebase Failed

After researching the Rust-to-WebAssembly toolchain, I found that wasm-pack makes the conversion straightforward. The tool handles generating WebAssembly modules and JavaScript bindings automatically. I started by trying to integrate wasm-pack directly into the existing Orchestrator codebase.

The compilation succeeded initially, but then the Rust compiler flagged functions as unused dead code. This confused me because these functions were essential—core audio synthesis functions like sine_oscillator and sine_orchestrator that I'd written specifically for WebAssembly exposure.

The investigation revealed the actual issue. In a Rust binary project, main.rs serves as the entry point and the compiler performs dead code elimination based on what main.rs calls. When compiling to WebAssembly, lib.rs becomes the entry point instead. The functions I'd exposed in lib.rs for WebAssembly weren't being called by main.rs, so the compiler correctly identified them as unused from the binary perspective.

The same codebase was trying to serve two different purposes—a CLI binary with main.rs as the root, and a WebAssembly library with lib.rs as the root. This created architectural conflicts. I could have used conditional compilation flags or other workarounds, but the cleaner approach was obvious: create a separate project structured specifically for WebAssembly from the start.

Building a Monorepo Architecture

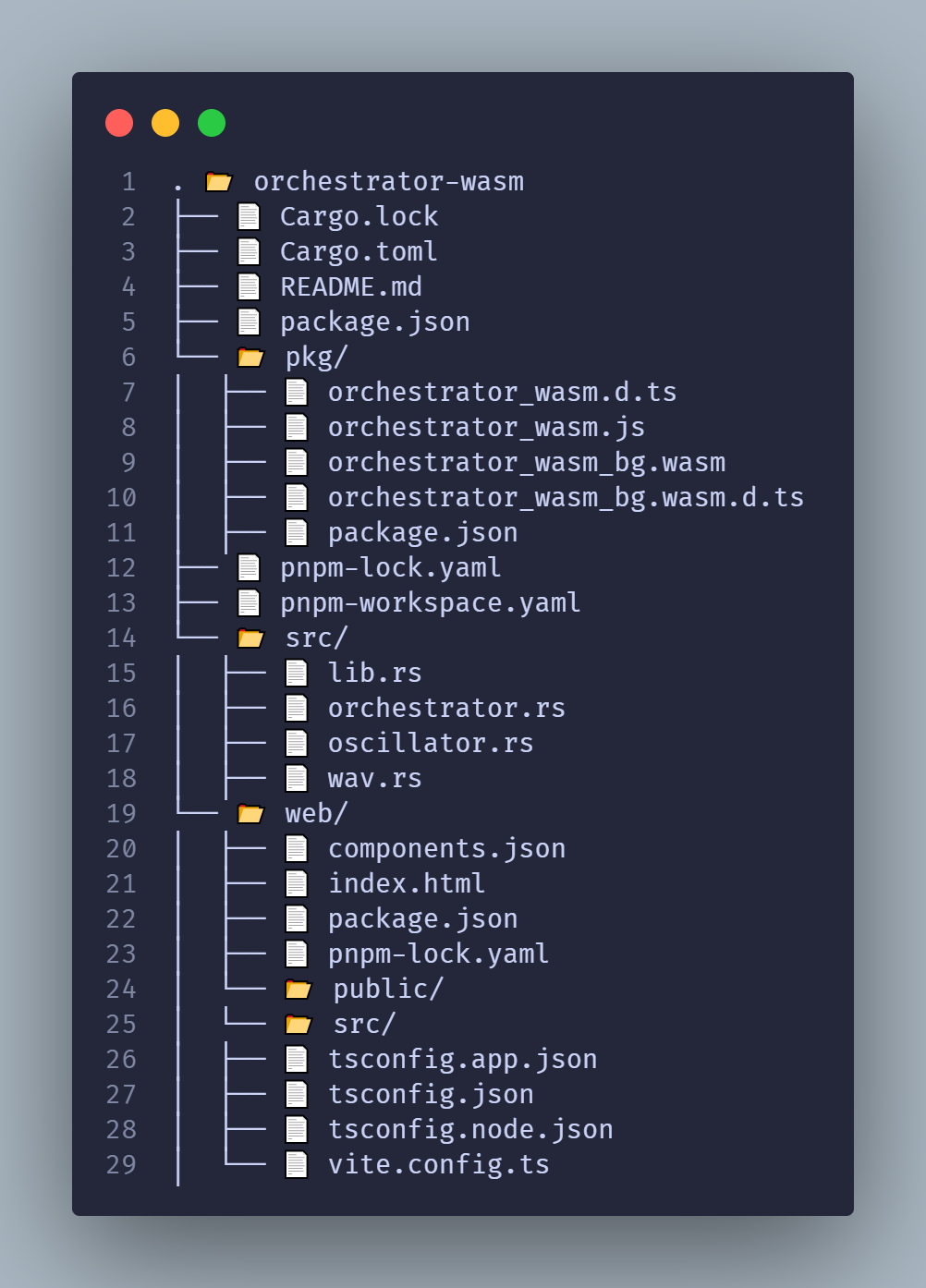

Starting fresh gave me complete control over the project structure. I initialized the Rust project as a library rather than a binary, which meant only lib.rs existed as the entry point. No main.rs to create compiler confusion.

When wasm-pack compiles the Rust code, it generates the WebAssembly module and JavaScript bindings into a folder called pkg. This output is essentially a JavaScript package. I created a pnpm workspace at the project root, added a new web folder for the React application, and registered both pkg and web as packages in the workspace. This monorepo structure meant the web application could import the Rust-generated WebAssembly module like any other npm package: import orchestrator from 'orchestrator_wasm'.

The architecture eliminated the complexity of managing separate repositories or complicated build pipelines. The Rust code, generated WebAssembly artifacts, and React frontend all lived in the same repository with clearly defined boundaries.

Making Music Creation Intuitive

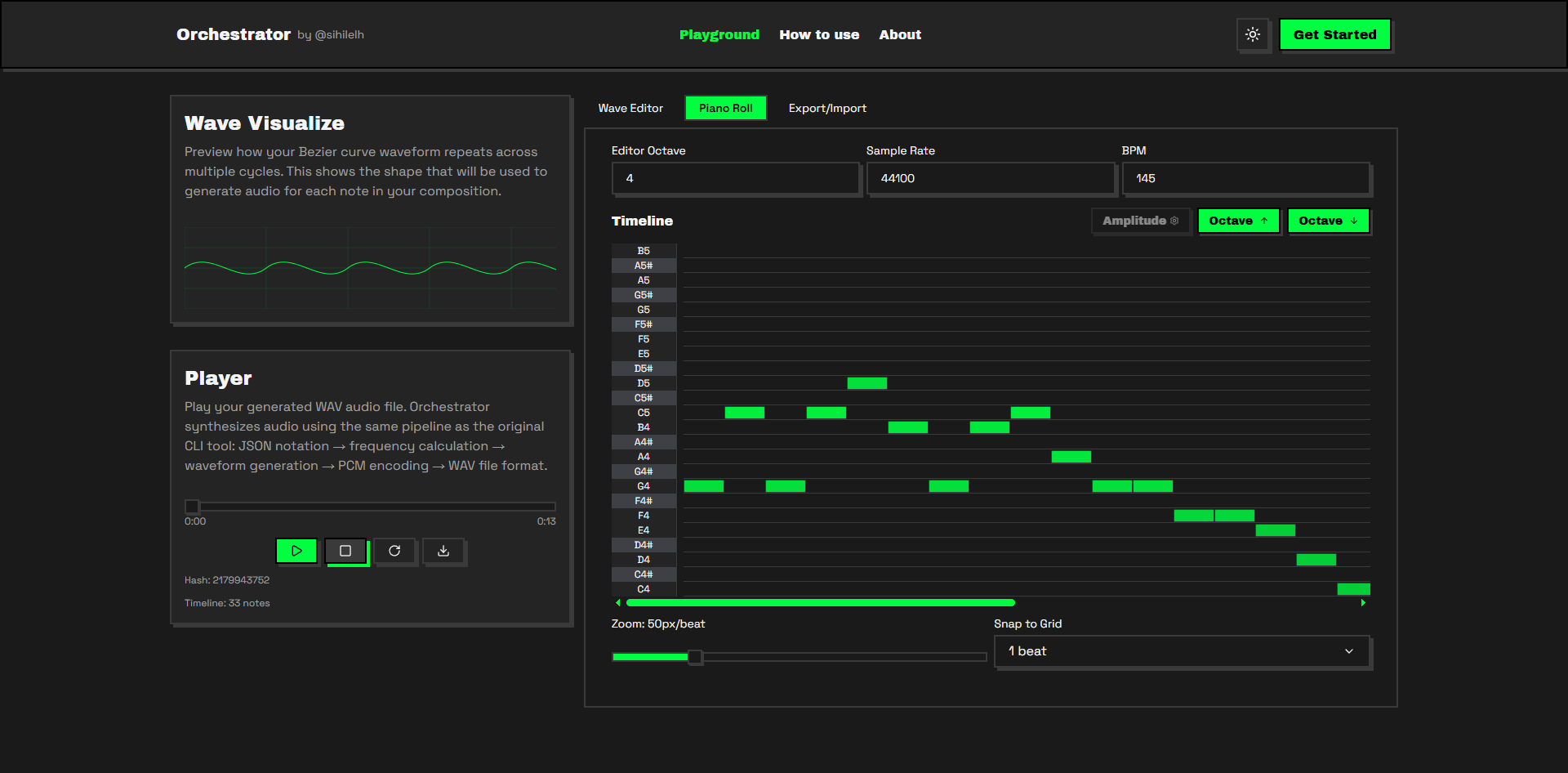

Compiling Rust to WebAssembly and importing it into React was straightforward. The harder challenge was creating a user interface that made music creation feel natural. Command-line tools require users to understand JSON syntax and musical notation simultaneously. A web interface needed to be visual, immediate, and forgiving.

I chose React because its component model maps well to musical interfaces. For the UI component library, I wanted something with character—specifically a retro or neobrutalist aesthetic. I discovered that shadcn isn't just a component library but a design system that can be adapted to different visual styles. Retro UI is a shadcn-based registry implementing neobrutalist design patterns. The bold borders and high contrast gave the interface the personality I wanted.

Building the Piano Roll Timeline

The piano roll interface was the most technically demanding feature. A piano roll allows users to place, resize, and move notes on a time-versus-pitch grid. I implemented drag-and-drop and resizing using the react-rnd plugin, which provides the primitives for resizable and draggable components. But the timeline logic and state management were entirely my responsibility.

My first approach seemed logical: maintain a single array in a Zustand store representing all notes on the timeline, including both audible notes and silence. Music isn't just about the notes you play—it's equally about the space between them. The Orchestrator audio engine doesn't have a dedicated silence note type, so I tried representing silence as notes with zero amplitude, zero octave, and note ID zero.

This created complexity. Managing an array where some entries represented real musical notes and others represented the absence of sound made the editing logic fragile. Adding a note required calculating whether it would overlap with silence or other notes. Deleting a note meant either replacing it with a silence entry or recalculating the entire timeline.

I rethought the data model entirely. Instead of one timeline, I created two: a visibleTimeline array storing only the notes the user explicitly added, and a computed timeline array representing the complete audio timeline with silence filled in programmatically. When the user modifies the visibleTimeline through the piano roll interface, the application recalculates the full timeline with appropriate silence segments inserted.

This separation clarified everything. The visibleTimeline serves as the source of truth for the UI and for import/export operations. Users can export their composition as JSON compatible with the CLI tool and import JSON files to restore the editor state. The computed timeline feeds properly formatted data to the audio synthesis engine. The visible representation and the audio representation no longer had to share the same structure.

I also added controls for BPM and sample rate, giving users control over tempo and audio quality. This took over two days total to implement properly, but it transformed the interface into something that felt like a real composition tool.

Managing Browser Memory with Blob Objects

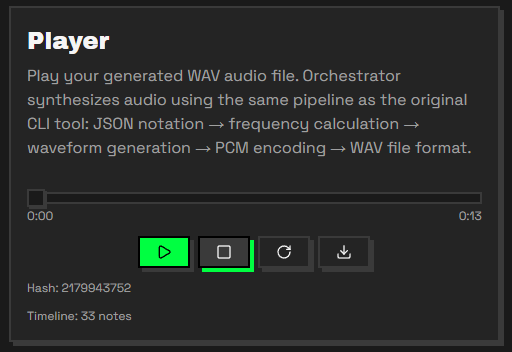

With the piano roll working and audio synthesis functioning through WebAssembly, I started testing continuous editing and discovered a new challenge: memory management in the browser.

Every time a user modifies the timeline, the synthesizer regenerates the audio. This is necessary for immediate feedback, but it means audio generation can happen multiple times per second during active editing. Each generation creates a Blob object containing the WAV file data, and the browser creates a URL pointing to that Blob so the audio player can access it.

Blobs and their associated URLs consume memory. If you create new Blobs without explicitly revoking the old URLs, you create a memory leak. The browser's garbage collector will eventually clean up orphaned Blobs, but "eventually" isn't good enough when generating new audio data several times per second. Memory usage could spike during an editing session, potentially causing the browser to slow down or crash.

Every time the synthesizer generates new audio, I now explicitly call URL.revokeObjectURL() on the previous audio URL before creating a new one. This tells the browser it can immediately free the memory associated with the old Blob rather than waiting for garbage collection. Performance in web applications isn't just about execution speed—it's also about resource lifecycle management. WebAssembly gives you near-native computation speed, but you're still operating within the browser's memory model.

What I Built

The finished application is live at https://orchestrator.sihilel.com. Users can create music using the piano roll interface, adjust synthesis parameters, and export their compositions as JSON or audio files. The entire audio synthesis pipeline runs in WebAssembly, bringing the same low-level control I had in Rust to an interface that requires no installation.

The source code is available on GitHub. I'm certain there's room for improvement, and I welcome contributions or feedback from anyone interested in audio synthesis or WebAssembly.

Sometimes the wrong approach teaches you more than the right one. Trying to retrofit wasm-pack into the existing codebase failed, but that failure clarified how Rust's build targets work. The single-array timeline approach failed, but that failure forced me to separate concerns properly. The memory leaks taught me about Blob lifecycle management in a way that reading documentation never would have.

Building the CLI tool taught me how audio synthesis works. Building the web version taught me how to bring that knowledge to users in an accessible and immediate way.

P.S.: I later added a feature to customize the shape of the generated waveform using Bézier curves, which required building an entirely separate processing system. That's a story for the next post.